The Brain-Gut Connection and Probiotics

Share

Your brain talks to your gut, and your gut talks back. If you’ve ever had a “gut feeling,” you’ve experienced this communication. It’s how the thought of an exciting event can make you feel “butterflies in your stomach,” while the thought of something dreadful might be “gut-wrenching.”

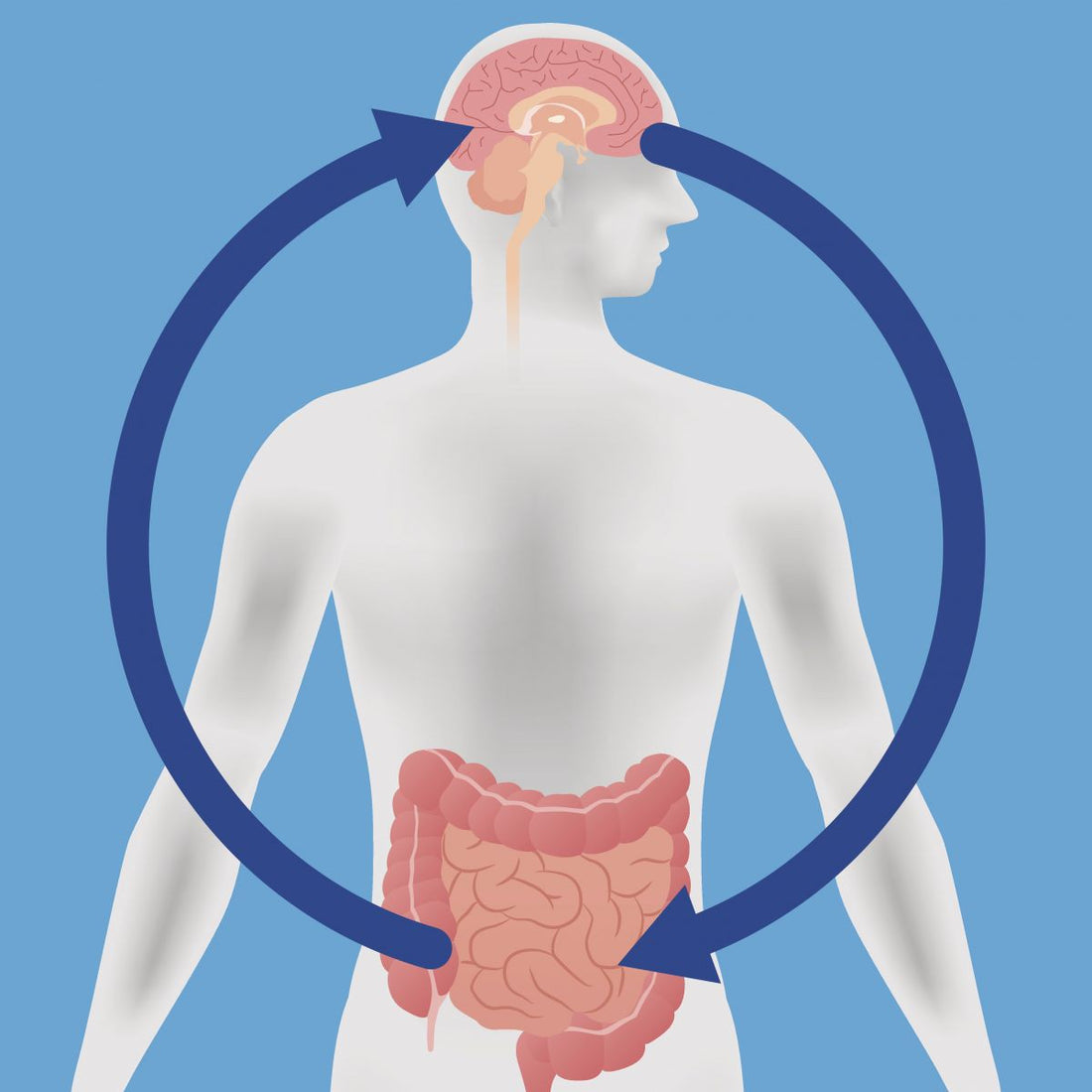

Research shows that the gut and brain are connected, a partnership called the gut-brain axis. The gut microbiome and the brain communicate to each other via the vagus nerve and it’s a two-way street. When the microbiome is off-balance, it can communicate the wrong messages to the brain and body.

The gut has been called a "second brain" because it produces many of the same neurotransmitters as the brain does, like serotonin, dopamine, and gamma-aminobutyric acid, all of which play a key role in regulating mood. In fact, it is estimated that 90% of serotonin is made in the digestive tract.

What affects the gut often affects the brain and vice versa? When your brain senses trouble—the fight-or-flight response—it sends warning signals to the gut, which is why stressful events can cause digestive problems like a nervous or upset stomach. On the flip side, flares of gastrointestinal issues like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), Crohn's disease, or chronic constipation may trigger anxiety or depression. These new findings may explain why a higher-than-normal percentage of people with IBS and functional bowel problems develop depression and anxiety. That’s important data, because up to 30% to 40% of the population has functional bowel problems at some point.

The brain-gut axis works in other ways, too. For example, your gut helps regulate appetite by telling the brain when it's time to stop eating. About 20 minutes after you eat, gut microbes produce proteins that can suppress appetite, which coincides with the time it often takes people to begin feeling full.

How might probiotics fit in the gut-brain axis? Some research has found that probiotics may help boost mood and cognitive function and lower stress and anxiety. For example, a study published by Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience found that Alzheimer's patients who drank milk made with four probiotic bacteria species for 12 weeks scored better on a test to measure cognitive impairment compared with those who drank regular milk.

And a small study reported in the journal Gastroenterology found that women who ate yogurt with a mix of probiotics twice a day for four weeks were calmer when exposed to images of angry and frightened faces compared to a control group. MRIs also found that the yogurt group had lower activity in the insula, the brain area that processes internal body sensations, like those emanating from the gut.

It's too early to determine the exact role probiotics play in the gut-brain axis since this research is still ongoing. Probiotics may not only support a healthier gut, but a healthier brain as well.

Source(s): Harvard Health/ Hopkins Medicine